non-stationarity and adverse selection

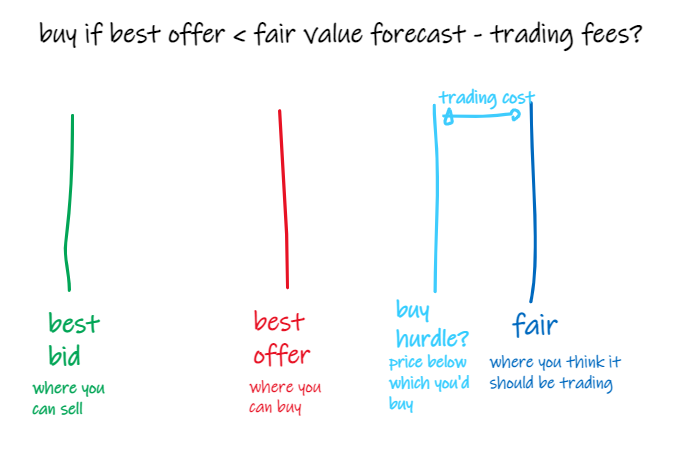

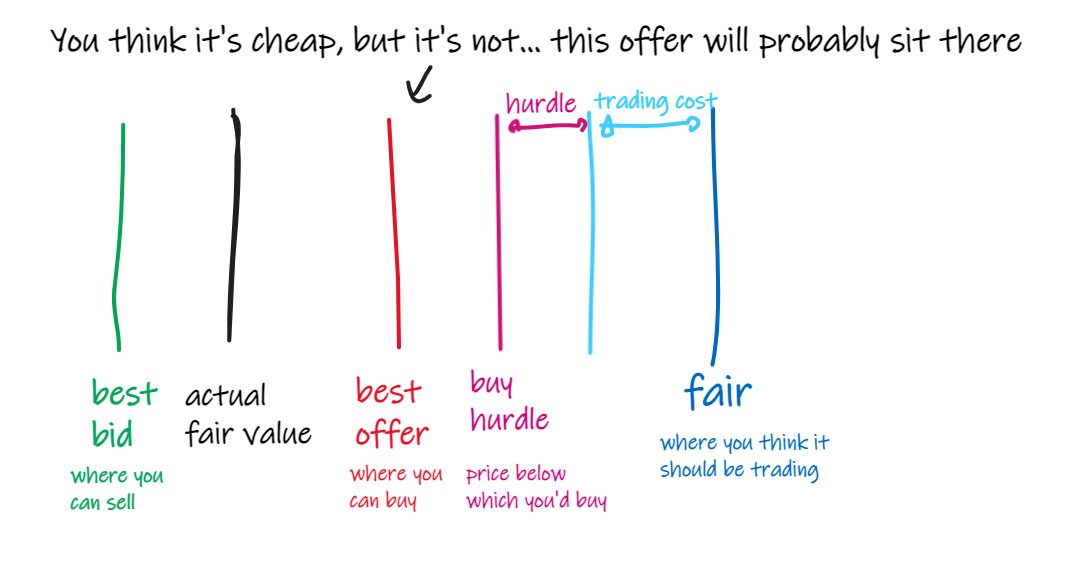

you predict the fair value of some instrument: where you expect it to be trading in the future if nothing else happens

if there's an offer to sell it cheaper than your fair value forecast, you might consider buying it (lifting the offer)

but you pay fees to trade, especially if you are taking liquidity like this.

so, you need to factor this in.

now you need someone offering to sell the instrument at less than your fair value, less your costs to trade.

and you don't want to put on risky positions for tiny returns.

and sometimes you're wrong.

so, you better get some wiggle room in the trade: get a hurdle in there.

now you need someone offering to sell at less than your fair value, less your costs to trade, less a hurdle.

if your forecast is good, and the market is inefficient enough that you get the opportunity to fleetingly trade with someone at bad prices, you have the basis for a trading strategy.

so you simulate buying if it's offered less than your forecast, less trading cost, less a hurdle.

to keep things simple, we'll assume that you magically get out of each trade at midpoint t minutes later.

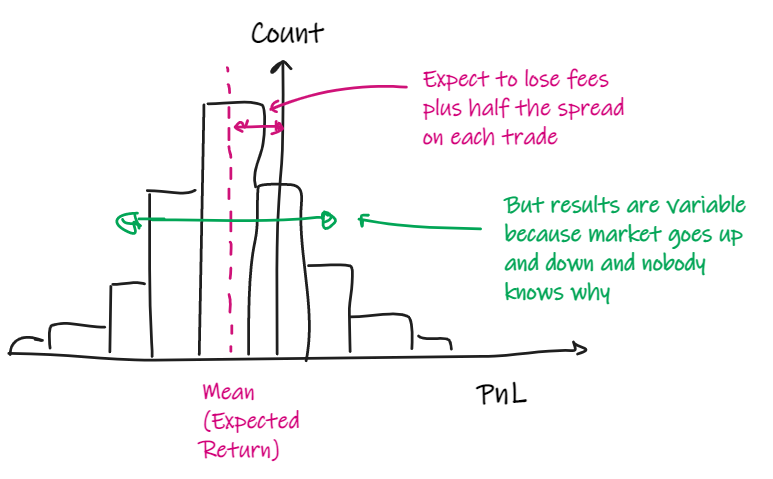

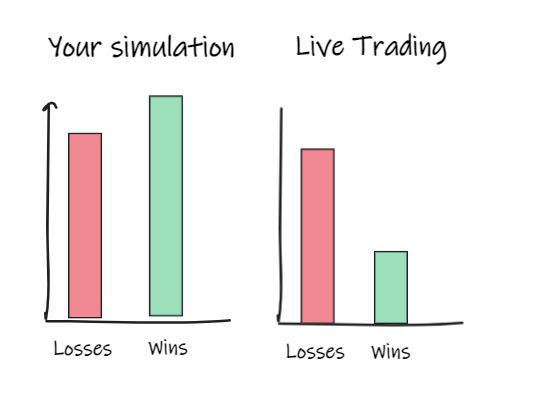

you do your simulation and plot a histogram of trade PnL.

if your forecast is useless it will look like this:

you'll be losing fees and half the spread on each trade, on average.

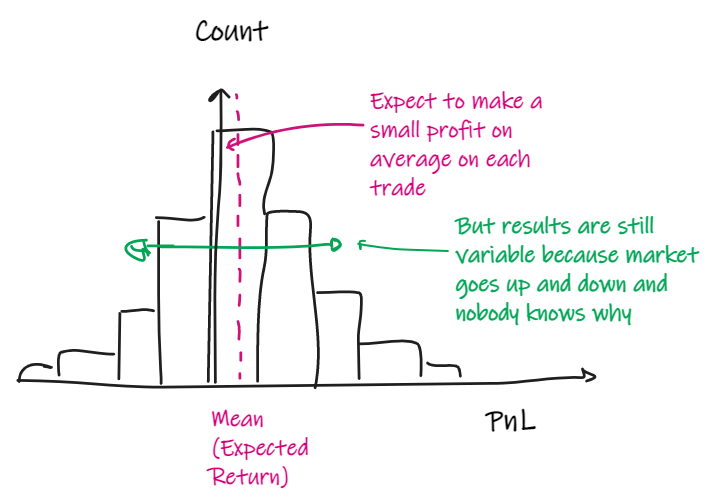

but if your forecast is decent it might look like this:

"cool," you say. "i understand my edge now.

"i understand that market outcomes are mostly random, and that is represented in the spread of my histogram.

"but, if I take enough bets, all that will net off and I'll realize my expected return"

nearly right

but actually very not right.

you find this out when you start trading and start losing money.

what happened? the simulation looked fantastic!

"must have overfitted" beginners often suggest.

but it's probably not that, unless you did something really dumb.

(and don't do really dumb overfitty stuff)

it likely has more to do with these two things:

- non-stationarity

- adverse selection

first, non-stationarity...

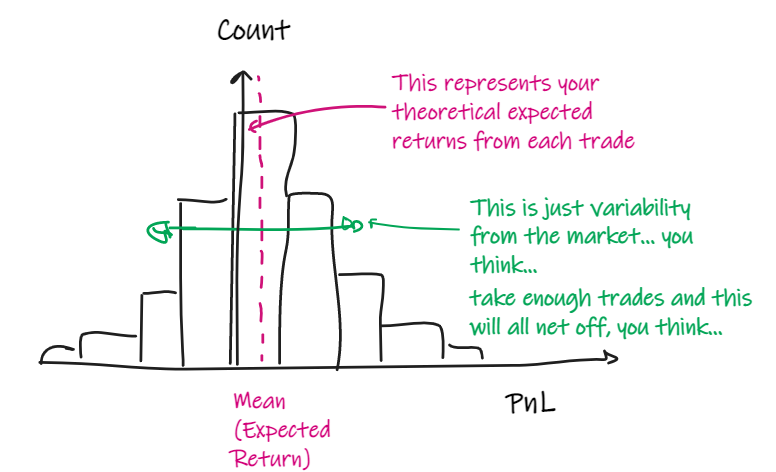

when you plotted that histogram and thought that it represented your edge, you implicitly assumed that your edge was the same for every single trade.

and that the variance in outcomes was solely due to the unforecastable market moves.

that's the best-case scenario.

in fact, sometimes you're just wrong.

however good your forecast is, there will be non-random stuff you haven't modelled.

so sometimes you're trying to take good trades, and sometimes you are trying to take bad trades

you're not pulling returns out of the same histogram each trade.

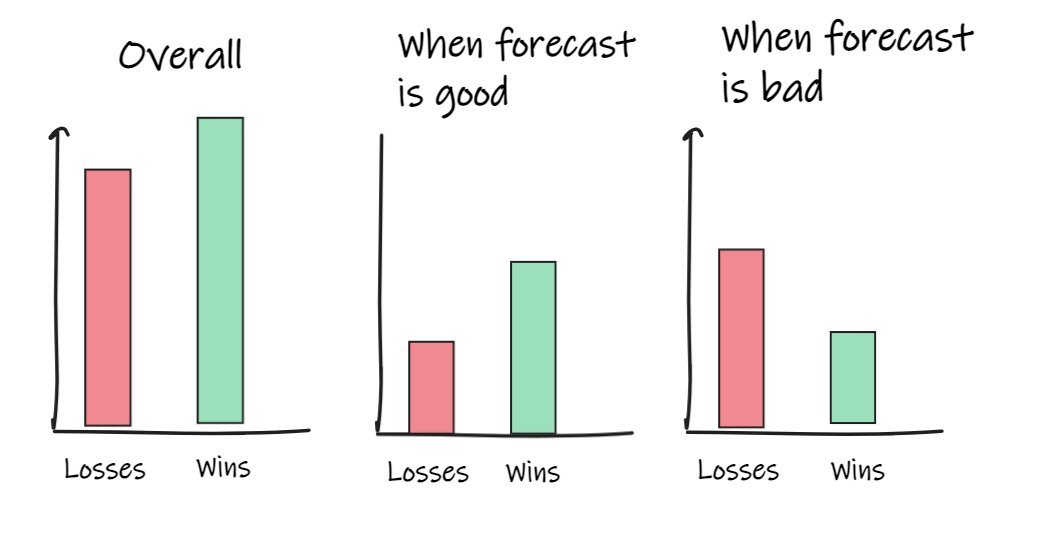

let's simplify to two states:

- Your forecast is good

- Your forecast is bad

and, to make it easier for me to draw, let's now assume our wins and losses are symmetrical.

when our forecast is good we have more wins than losses.

when it's bad we have more losses than wins.

your simulation results were good, so you know that your forecast was more often good than bad.

but in live trading, your results were bad.

you run your simulation back over that same data, and you find the simulation takes more trades than you took in live trading.

you aggregate the trades from simulation and live.

and you see that, in trading, you took most of the losing trades but you missed a lot of winning trades.

what happened?

competition. adverse selection.

consider the case when your forecast is good.

you think the instrument is being offered cheap, and you're right.

others will also think it's cheap.

so you're going to be in a race with other smart traders to lift that offer.

to win that race, you must be either:

- faster (respond to obvious stuff quickest)

- smarter (predict it before others)

- prepared to take on lower edge bets than others

- lucky (win on a random component, such as network jitter)

so, when you're starting out, you're going to lose a lot of races for the good stuff.

that's why you missed a bunch of good trades. it's a highly competitive environment out there.

now consider the case when your forecast is bad.

you think the instrument is being offered cheap, but it's not.

other smart traders are unlikely to think it's cheap.

so, there won't be much of a race for this. The offer is likely to sit there for you to take.

this is why you took so many of the losing trades in live trading.

when your forecast was bad, your trades were uncompetitive, so you took most of them.

when your forecast was good, your trades were highly competitive, so you missed lots of them.

this is an example of "adverse selection".

good opportunities are highly competitive.

just because you could see a price was available for someone to take, doesn't mean you could have taken it. you probably couldn't, unless you put a huge amount of work in.

if trading like this sounds like a massive amount of work, that's because it is.

you either need to be:

- the fastest (not much left for #2 in straight races)

- very fast with better forecasts than the fastest

- fast, with good forecasts, willing to trade sparse edge cases

1 and 2 is a large business.

i mostly play at 3, in murky places.

i wouldn't recommend you do tho, unless you're a maniac. it's a constant battle to stay competitive.

there are more forgiving ways to trade and invest.

but if you're reading this, you're probably a maniac too.

so, good luck out there.

beep...boop.